Winifred Hodge Rose

Thor as the Farmer’s God

I can’t agree at all with the portrayal of Thor as a thick-headed oaf or as nothing but a hammer-swinging brute. I have experienced him many times in the form of a down-to-earth yeoman farmer, wise in the ways of the land and the needs of everyday life. Farmers, too, were often looked down on and disrespected by ‘aristocrats’ of various types. Yet, a successful subsistence farmer must be wise and disciplined in many ways: when and how to plant or slaughter; how much to eat now and how much to save for future planting or breeding. How to make best use of scarce resources. How to adapt to weather and climate. Careful planning and disciplined execution of those plans. Fair management and guidance for all the folk of the farm, and training for the youngsters. The skills of breeding and selection, planning for the future.

Thor has shown me time and again that he can guide the practical management of resources, any resources, and lend his power in the execution of the resulting tasks. His strength supports us in dealing practically with the unexpected, with challenges and even disasters of all kinds, with scarcity as well as abundance. He leads us away from being helpless whiners, overwhelmed by life. He’s a Can-Do God, and his children follow him in that. Anyone who wants to make a success of their practical, everyday life will benefit from working with Thor and his family members Sif, Thruðr, Magni and Moði.

The old Heathen poets don’t talk about these ordinary down-to-earth things except to scoff at them, but the fact that Thor is called the farmer’s God says a lot when we understand what farming is all about: rolling up our sleeves and digging down into the fertile soil of everyday tasks to make a good life out of what we have.

The Thorlings: Thor’s Children

First, some definitions:

Thorlings: A term I invented, based on the Germanic suffix “ling, lingas” that implies ‘belonging to or descended from’ the name the suffix is attached to. Thus, Thorlings or Thorlingas are those who are descended from Thor: Magni, Moði and Thruðr.

Thruðr: Daughter of Thor and the Goddess Sif. Her name means ‘Strength’. Presumably she, like her brothers Magni and Modi, survives Ragnarök and becomes one of the leaders of the new world. Her father’s Godly domain bears her name: Thruðheim or ‘strength-home, strength-world.’

Magni: A son of Thor and the giantess Jarnsaxa, embodiment of might and main. He survives Ragnarök and is one of the leading Deities of the new world that comes after.

Moði: A son of Thor and the giantess Jarnsaxa, embodiment and channel of mod-power. He survives Ragnarök and is one of the leading Deities of the new world that comes after.

Mod, mod-power: I envision this as a form of energy similar to mægen / megin, except that it is shaped by the mood and character of the being who is accessing and expressing it.

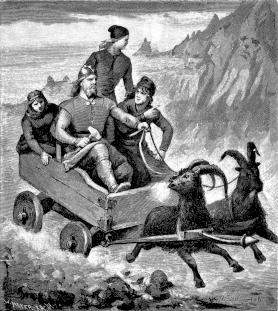

Thor with his children: Magni, Moði, Thruðr.

There is a kind of courageous, driving, powerful energy within us, and within other beings and the environment as well. This power was often called mod, but also called mægen in the ancient Germanic languages, and very often these terms were used together, to give a complete picture of a powerful form of energy that can be directed by our Mod-soul. These two terms come together perfectly in the names of Thor’s and Jarnsaxa’s sons, Magni (main, mægen) and Moði (mod-y, filled with mod), and are further enhanced by the name of Thor’s and Sif’s daughter Thruðr or ‘strength’. Thor himself, of course, is the embodiment of mod, mægen, and strength as well. Let’s explore this mystery of power just a little further.

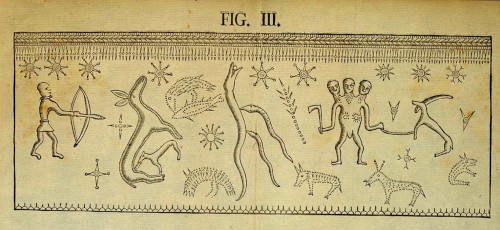

There is a strange figure of a three-headed man shown on the Danish Gallehus horn, who is generally thought to be Thor. He is holding a long-handled implement, an axe or a hammer, and with the other hand holds a rope tied to a horned and bearded animal, presumably a goat.

Three-headed figure from the Gallehus horn.

Here are my own thoughts about this figure. I do believe it is Thor, and that the heads on either side of the central one represent his sons, Magni and Moði, with their powers which arise from his own. I think many or all of the figures on the Gallehus horn(s) show indications of mystery cults or ritual patterns dedicated to various Deities, and that this three-headed figure represents one of those mysteries. It also points toward Thor’s mystery of his ability to slaughter and eat his goats and then raise them to life again by hallowing their bones with his Hammer.

The strange depiction of him with three heads, in my view, indicates both the multiplication of his mod-and-main power, and the budding of his offspring or emanations, Moði and Magni. All of these: budding or growing mod and main, sacrificing (the goat) to his need, and then bringing dead bones to life by hallowing with his Hammer, are part of Thor’s mystery. There is much to ponder here, as we seek to understand the full expression of mod and mægen, sacrifice and revival into life, and the great and complex powers of Thor expressed through his mighty Hammer.

Meditations, devotions, magical workings, and other focused attention on Thor and his children are very fine ways to develop and shape our own mod and mægen energies. It’s my opinion that modern Heathens would do well to pay more attention to the ‘Thorlings’ or Thor’s children, not least because they were / are / will be Ragnarök survivors and thus among the divine leaders of the next cycle of the Worlds. The idea that ‘mod, mægen and strength’ are focused through them and into the worlds, both now and later, is not a trivial consideration!

This leads us to another point: the phrase ‘mod and mægen’ together was how the ancient Germanic scholars translated the Latin term virtus or ‘virtue’, specifically the kind of virtue that refers to ‘special powers, outstanding potency’ of things like powerful herbs and magical implements. This understanding implies that the triple Thorlings, Modi-Magni-Thruðr / Mod-Mægen-Strength, can be called upon to imbue something with power and virtue in this sense, including our own souls but also magical and healing items and spells, among other things.

This may have been an underlying meaning of the rune-inscription wigi Thonar, ‘Thor hallow’, on the 6th-century Nordendorf fibulae: calling on Thor not only to make the inscribed item sacred or hallowed, but also to fill it with virtue and power, mod and mægen, for some special purpose. (See these three articles on this website: Wigi Thonar: The Powers of Thor’s Hammer; The Powers of the Dwarves; and The Living Jewels of Brisingamen, for more about hallowing, mod, mægen, and ‘virtue.’)

Magnetic Power

One of the ways we can build and channel mod-power in our lives is, in a sense, to work backwards. Instead of trying to grow mod-power directly, we can grow it through a process of ‘suction’ or ‘magnetism’. We do this by deciding where we most want to use our mod-power and then allowing our focus and dedication to these areas of life to pull our mod-energy and abilities in that direction. Once this magnetic power / energy starts flowing strongly, it helps to break up energy blocks and pinch-points that our life experiences and circumstances have created, which hamper our access to our own mod-power.

Thinking about magnetic mod-power leads us toward the similarity between ‘magnet’ and Magni Thor’s son. The word ‘magnet’ comes ultimately from Magnesia, a region named after one of the demigod sons of Zeus Thunder-God, Magnes, who was considered the founding-father of the ancient Greek tribe which settled in that region of northern Greece. Magnetic ore was found here and was called ‘the stone of Magnes.’ (Online Etymology Dictionary.)

Here we have two powerful sons of the Thunder-Gods Thor and Zeus, with basically the same name, Magni and Magnes, associated with the word for magnetic iron. This leads us to a connection with Thor’s mighty iron Hammer and its flows of power, and likewise with Zeus’s great Thunderbolts.

Looking at the Thorling brothers Magni and Modi, we have the combined power of mod and main or mægen associated with the power of magnetism. For myself, these energies feel profoundly real and meaningful both within and around me, and draw me toward the Thorlings as powerful Gods to work with when seeking to understand and use such energies.

Moði represents and helps us channel our mod-power. Magni represents the magnetic force that can pull out mighty flows of that mod-power in a direction that we choose. Their sister Thruðr, ‘Strength’, represents the strength of character and Will needed in order to direct these powers rightly. Moði is the ‘substance’ of Mod, Magni is the ‘force’ of that substance, and Thruðr is the ‘form’ that shapes the expression of the substance and the force.

Thor himself ties all of them together: a God not only of might and main, but also a God of trustworthy character, of right and beneficial action, and a God whose actions are powerful and effective. All of them can support and help direct our efforts to grow and shape our powers of mod and mægen, character and will. Through all of them we can learn more about how these powers express themselves in Nature, people, and the many holy Powers of the Worlds.

Thor’s Act of Compassion

Few of us, perhaps, would think of Thor as an example of divine compassion in our faith, but I suggest this is worth considering! It all depends on understanding how different beings—Gods, people, ancestors—express their compassion, and such understanding depends in turn on one’s culture and expectations of compassion. I would say that elder Heathen cultures focused much more on compassion as practical action, as we see so often from the German Goddess Frau Holle / Holda for example, rather than on compassion as an emotional exchange of feelings.

Here is one non-obvious example of such godly compassion from our lore (from Gylfaginning in the prose Edda, Sturlason p. 38). In this tale, Thor stops overnight with a peasant family, slaughters the goats who draw his chariot, and shares their meat with the family. Unbeknownst to him, however, the son breaks a leg-bone for the marrow. When Thor waves his Hammer over his goats to restore them to life the next morning, he discovers that one of them is limping. Thor falls into a mod-fury—Asmoði, the ‘mood of the Æsir’—and threatens the family in revenge. But he is not in a blind rage: when he sees the family’s terror, he sefadiz, he shifts from the raging of his Asmoði state into the compassion and calm of his sefa-soul and agrees to accept compensation rather than enact revenge.

The family offer their son and daughter to Thor as their compensation, and from our modern perspective this does not seem like a compassionate outcome. Look at it from the perspective of the society at that time, however. For peasant children to be taken into service with a great Deity would be the ultimate dream come true, an honor and benefit to the whole family.

Thjalfi gained fame and reward as a brave and trusty companion of Thor on his adventures, something he would never have achieved as a laboring peasant, no matter how hard he worked. His sister Roskva goes with them on their next adventure, but we don’t hear more of her after that. I assume she eventually joins the household of Thor’s daughter Thruðr, or his wife Sif, and gains the many advantages of greatly enhanced social status.

The ‘compensation’ Thor accepted was, in truth, a continuation of his compassion and his blessing for the family, as indeed was the original sacrifice and feast of his goats to feed a poor peasant family (as well as himself, of course!). Instead of slaughtering or cursing the family for their transgression, he improved their lives.

Thor was a much-trusted God in the past, and is certainly so among Heathens today. I suggest that we expand our understanding of, and work with, his children as well. The Thorlings are worthy scions of the family line; long may their power and their honor endure!